TYSONS OFFICE

California Inheritance Tax: What You Actually Owe (and What You Don’t)

If you’ve inherited a home or assets in California, you may be unsure what taxes apply or whether you need to prepare for a California inheritance tax. Many people are surprised to learn that the rules in California work differently than in other states. The most significant tax concerns often involve federal estate rules, property tax reassessment under Prop 19, and capital gains tax.

So what does that actually mean for you as a beneficiary? Let’s start with the question most families ask first: How much is inheritance tax in California?

How Much is Inheritance Tax In California? The Answer Might Surprise You.

Many people brace themselves for a big tax bill after inheriting property, but in California, there is currently no inheritance tax. Whether you receive a small savings account or a multimillion-dollar home, the state does not tax you simply because you inherited it.

That means:

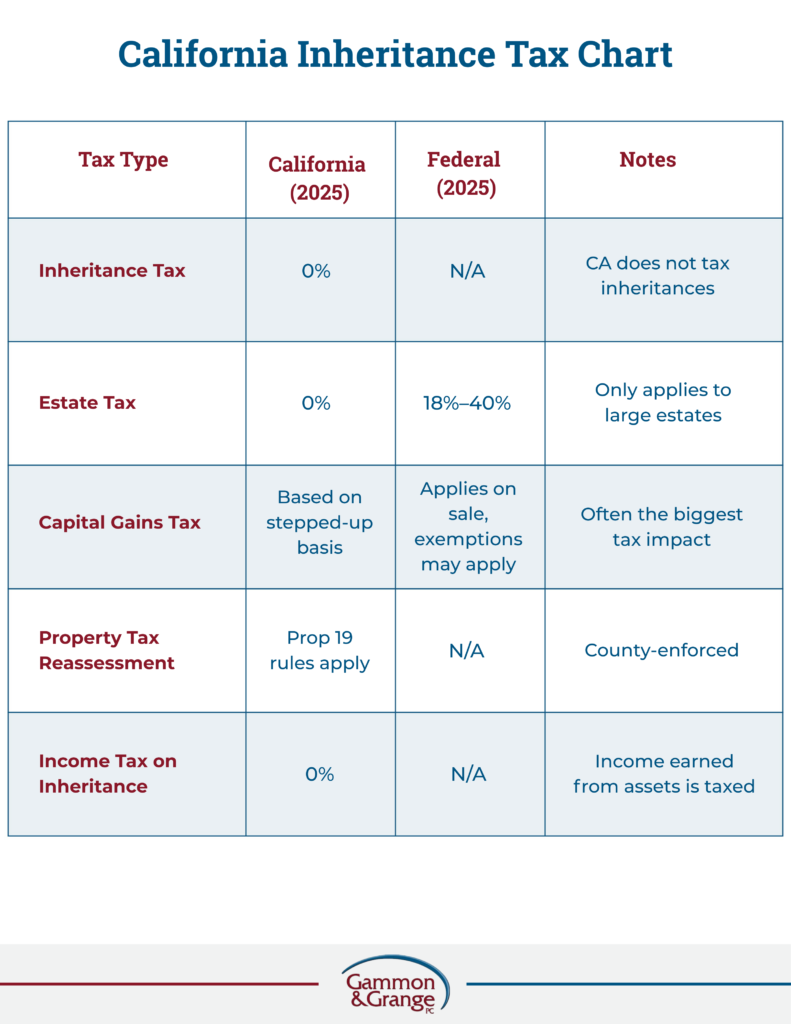

- 0% state inheritance tax

- 0% California estate tax

- No state income tax on inherited assets

But that’s not the whole story. You may still face other taxes depending on what you inherit, whether you sell it, and how you use it. Let’s look at what actually can trigger taxes at the federal level or through property reassessment.

Federal Estate Tax: Who Actually Has to Pay It?

Since California doesn’t tax inheritances, the only “death tax” most families ever worry about is the federal estate tax — and it applies only to estates worth over $13,990,000 in 2025 (or $27,980,000 for married couples who plan correctly). Anything above that amount gets taxed at up to 40%.

Most Californians will never owe this, but high real-estate values and large life insurance death benefits mean some families should pay attention. Here’s what to remember:

- Spouses don’t pay — everything left to a surviving spouse is tax-free.

- To keep the full two-spouse exemption, the survivor must file IRS Form 706 within required time frames so the first spouse’s unused exemption can be “ported” over. Please contact a tax attorney for assistance.

Once you know whether federal estate tax applies, the next key question involves California Prop 19.

Understanding CA Prop 19 and Property Tax Reassessment

Under CA Prop 19, inheriting a home can lead to a major property tax jump unless the child (or grandchild, in limited cases) moves into the property and files the required forms within one year. If the home was not the parents’ primary residence—or the inheritor chooses not to live there—the county will reassess the property at full market value on the date of death.

This reassessment isn’t delayed or optional. It typically takes effect on the next lien date after the parent’s death—usually January 1 of the following year. The inheritor will begin paying the higher tax bill in the next regular tax cycle unless they move into the home as their primary residence and file for the Homeowner’s Exemption and Prop 19 Exclusion Claim on time.

Read our blog to learn more about how to avoid property tax reassessment under CA Prop 19. While property tax reassessment can bring unexpected tax surprises, so can the capital gains tax that comes if you choose to sell your inherited property.

Understanding Capital Gains Tax and Inherited Property

While California and the IRS don’t tax the money or property you inherit, they can tax any income those inherited assets produce when that income is realized. That means while the inheritance itself is tax-free, what you earn from it may not be when realized through a sale or other receipt of income. For example, rental income from an inherited home is taxable, dividends from inherited stocks are taxable, and profits from selling inherited property may be taxable. The key to understanding this is something called the step-up in basis.

When a parent passes away and leaves a home to you in a will or trust, the tax basis of their home or investments is “stepped up” to the property’s value on the date of death. This can save heirs a tremendous amount in taxes.

For example, imagine your parents bought a home in 1980 for $10,000, and it’s worth $1 million when you inherit it. If you sell the home right away for the same $1 million, you owe zero capital gains tax because your basis stepped up to $1 million at the date of death. In addition, homeowners may qualify for a federal capital gains tax exemption, which currently allows a single taxpayer to exclude up to $250,000 and married taxpayers to exclude up to $500,000 of capital gain income.

If you hold onto the home and sell later for more, only the increase after the date of death is taxable. So if you sell for $1.2 million, your taxable gain is just $200,000, and you may even be able to exclude up to $250,000 ($500,000 if married and filing jointly) if IRS requirements are met.

This is why many estate planning attorneys urge families not to gift homes during life unless they fully understand the tax consequences and eligibility/filing requirements for the benefits.

Tax Implications of Lifetime Gifting

Giving a home to your child while you’re still alive can sound like smart planning, but it often creates much larger capital gains taxes later. That’s because lifetime gifts pass down your original tax basis. If you bought a home for $10,000 and gift it today, your child inherits that same $10,000 basis — and selling the home for $1 million could leave them with nearly $990,000 in taxable gain.

That said, lifetime gifting can make sense in certain situations.

Under 2025 federal rules, you can gift:

- Up to $19,000 per person with no tax and no Form 709

- Anything over $19,000 with no tax owed, but you must file Form 709

- Gifts above this amount count toward your $13,990,000 lifetime exemption (or $27,980,000 for married couples). This threshold changes and will be $15,000,000 starting in 2026.

This means you could gift a $300,000 home with no federal gift tax applied to your heir, but it may result in a larger capital gains tax payment for your heir later.

In most cases, the tax savings from inherited property (thanks to the step-up in basis) far outweigh the short-term benefits of gifting real estate during life. Always check with a CA estate planning attorney before choosing this route.

California Inheritance Tax Chart at a Glance

FAQs About California Inheritance Tax

Does California have an inheritance tax?

No. California has 0% inheritance tax.

Do I pay income tax on inherited money in California?

No, but income generated by inherited assets is taxable when realized.

Do I pay taxes when selling an inherited home in California?

Only if you sell it for more than its value on the date of death (after applying the step-up in basis).

Can Prop 19 increase my property taxes?

Yes. If you inherit a home and do not move into it or miss filing deadlines, the county will reassess it at full market value.

Do trusts avoid inheritance tax in California?

There is no California inheritance tax — and trusts don’t change federal estate tax rules.

How can I reduce taxes on inherited property in California?

Live in the property as your primary residence before selling.

Keep real estate inside a trust (rather than gifting early).

Follow Prop 19 filing rules.

Consult an estate planning attorney for capital gains planning.

Final Takeaways

While California doesn’t tax inheritances, the rules surrounding estate tax, capital gains, and property tax reassessment can still feel confusing and stressful.

As a California estate planning attorney, I’ve seen firsthand how overwhelming this can feel — and how much relief the right plan can bring. With proper guidance regarding California inheritance law, most families can protect their tax base, minimize surprises, and honor their loved one’s legacy in the way it was intended. If you’d like help understanding your tax exposure — or planning to reduce it — our team at Gammon & Grange is here to guide you.

This blog provides general information about inheritance tax and related topics in California and is for informational purposes only. It is not legal advice, does not create an attorney-client relationship, and should not be relied upon to make decisions about your specific situation. Readers should consult an attorney or other appropriate professional for advice tailored to their particular facts and circumstances.

Tax laws and thresholds change, and application of the law depends on individual facts; for guidance on your situation, please confirm current figures and seek personalized legal counsel from a licensed professional in your jurisdiction.